Author: admin

Carleton Farm and the Olin Farm

By Dani Reynoso, Sara Negasi and Bladimir Contreras

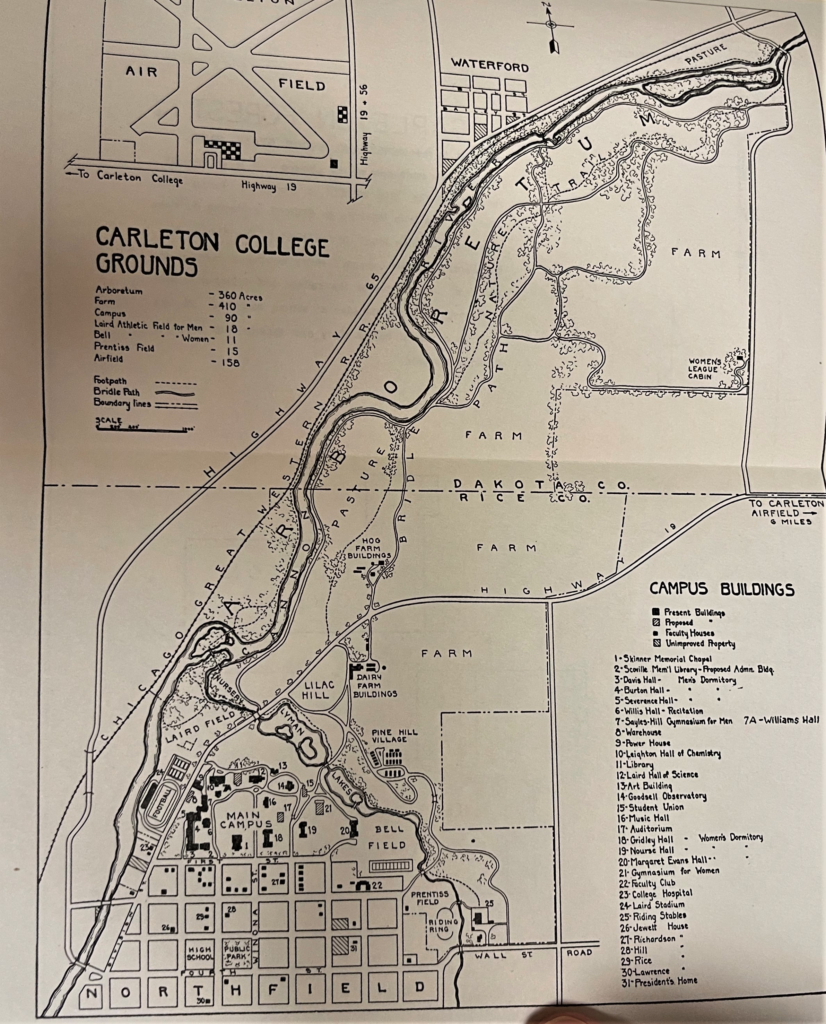

Our final project is focused on the Olin Farm during the period it functioned as a farm for Carleton College. We created a story map, here’s the link to it: https://arcg.is/0u4ee

Like many other Midwestern colleges at the time, Carleton took part in the purchase of farmlands in order to help provide for their student body. Carleton itself purchased multiple other farms in the immediate area to the Northwest of campus. Some of these include the Parr Farm, Peterson Farm, and Arnold Farm.

Our project is focused specifically on the Olin Farm area, which is the area labeled under ‘Hog Farm Buildings’.

The map below depicts the layout and dimensions of the Olin Farm with the farmhouse on the right and the hog barn, granary and chicken house on the left.

Our research question was guiding by the fact that so much is unknown about the Olin Farm separate from the Carleton Farm and so our goal was to try and learn what life was like on the farm for students and workers as well as to understand the purpose for Carleton’s purchase of the 100 acre farmland.

Our timeline begins with the purchase of the Olin property by Carleton in 1916. It was bought with the intention of being able to feed more students who were enrolling into Carleton and it was a very common purchase for the school.

The above article clipping is from the school’s newspaper that stated Carleton students were able to work on the farm to pay off their room and board. Other archived fiscal reports detail how the house was also rented out to people who would come to work on the farm. The last record of the house being rented out was in 1963 when a man named Norman Johnson paid $660 to rent the Olin residence for a year.

The above note addressed to President Cowling describes how the farm was becoming difficult to maintain thanks to crop failures and a decrease in income from the property. The 1964 letter below is from the Treasurer’s Office and it shows the decline of the Carleton Farms (including Olin) and the college wanting to rent the property.

The last financial record of the farm is from 1964 so we assume that the land was maintained by the school as a former professor currently occupies the house. It is also now part of the area that is known as the Cowling Arboretum, and so the land surrounding the house consists of a nature path.

—

Overall, he hope that our project is able to present and explain in an engaging way the history of the Olin farm from 1916-1960(ish). All the information above including texts, images and documents, can be used to explain possible functions of the Olin/Kelley Farm. Lastly, thank you for reading this far, we truly appreciate it. If you have any questions, comments, concerns, input, etc. regarding the entry above, feel free to reach out to us via email contreasb@carleton.edu, negasis@carleton.edu, reynosod@carleton.edu. We’ll be more than happy to connect with you 🙂

3-D Scans

A fragment of a bowl, with blue and yellow stripes not visible in the scan, found in excavation unit seven.

A fragment of a cow femur, found in excavation unit six.

Can, with church key indentations visible in top, found in test unit 11.

Timeline of Excavated Data

By Kyra Landry

Week 8 (Wednesday Lab)

During this week’s lab block, students in the Wednesday lab group were granted a third and final day of fieldwork, since last week’s rain had cost them one last week. We were fortunate enough to have good weather, but evidence of earlier rain could be seen in the fungal growth, wet soil, and speed at which the Cannon river flowed past the mill site. As in previous lab periods, students split up into working groups focused on DGPS mapping, locating and recording information about archaeological features, and continuing excavation in the two trenches. As this was the last day that either lab section would be working at the Waterford mill site, extra steps were taken at the end of the lab period to clean up the site. Particularly, all the metal stakes and bright pink tape that had been placed throughout the site during initial surveys were removed. Trenches were not backfilled, as we had not penetrated enough layers of soil for that to be necessary. Additionally, the state of the trenches after recent storms illustrated the speed at which they would soon be naturally filled.

Over the previous excavation days, several features were identified but only on the last day of lab were they fully mapped. This was both on paper, with sketches of each of the sites, and using the GIS mapping equipment. One of these features was the back wall of the second mill building, which was connected to another wall closer to the original site. In the process of following each of these formations, a pile of cans and various pieces of colored glass were found along one of the walls. The GIS team mapped each of these locations in order to get a more complete picture of the site. Another group was in charge of drawing some of the features and locations around the mill, such as the lower section of the main mill building closer to the water. Because of its proximity to the river and a rainy spring, we were not able to excavate there, nor were we able to excavate near the wall further along the river by the campfire. However, the GIS group mapped each of these locations as well, meaning future iterations of this class have a head start if they choose to do more excavations at the mill site.

The final day of excavation was quite productive, with both excavation groups getting through a good amount of depth, and putting several buckets worth of dirt through the sifter. Both excavation groups contended with the dampness of the soil as a result of recent rains, in addition to coming to the end of the high artifact density that near-surface excavation at this site yielded.The four students working in the first trench worked in subgroups of two, so that while one subgroup was sifting a bucket, the other was proceeding with the excavation and working on filling another bucket. The group working in the trash pit trench found, as in previous weeks, copious amount of charcoal and metal scraps, in addition to several pieces of glass, plastic and ceramic. Of particular note were a large metal item, which may have been an automobile component, a ceramic sherd that bore the name of the company that manufactured it, and a hollow, bulbous item that could have been either ceramic or rusted metal. Less was found in the second trench, as was consistent with the other excavation periods. Students excavating in the wall trench found a smattering of nails and metal shards, in addition to a large piece of a ceramic artifact. By the end of the excavation period, both groups ensured that they flattened the floors of their trenches, as well as removed the corner stakes and the perimeter tape surrounding their trenches. Trenches were left in such a state that nature could take its course in refilling them.

Week 7 (Wednesday Lab)

Img 1. Look at those branches!

Week 7 Summary by: Emily Moses and Sam Wege

Beautiful Weather, Drone Failure, a Deadly Tick, and a Fired .22 Casing

Sun!

“Under the Scorching Sun” – Maanya

Attempted Drone:

Though we tried to get drone data, due to restrictions around telephone lines and railroad tracks and general tree cover it wasn’t possible. Hopefully in coming weeks we can obtain drone footage.

Mapping:

Img 2. DGPS points from the Waterford Mill site on May 14 and 15

Img 3. Clarissa and Loren mapping with the DGPS

Findings:

Pictured below are some of the findings from trench 2, which are explained in the trench 2 section.

- Img 4. Findings from trench two, featuring nails, shells, a shard of bone, and a fired .22 bullet casing

- Img 5. Dirt from trench two being sifted to find its artifacts

Trench 2: Context 3

Img 6. Trench 2 before Wednesday’s excavation

Annie, Aaron, Clara, Hank, Emily and Sam excavated in Context 3. This was the first time excavating for all of us (Aaron was our mentor as he was an experienced trowler from his previous work in Israel and Jordan with Barbara). As Sam mentions in his fieldnotes, previous groups had mislabeled contexts which made it confusing to identify the context Wednesday’s lab was working in.

After establishing context 3, they began excavating working as flat as possible to evenly excavate the site. This was challenging, as it was tempting to dig in areas where there were clearly artifacts protruding. Additionally, as Clara mentions, there were possibly too many cooks in the very dirty kitchen which made communication very important–making sure that everyone was still troweling and clearing at about the same level. Each excavator used a trowel and dust tray–holding the trowel at 90 degrees in order to disturb the stratigraphic layers as little as possible–and swept thin layers of dirt into the pan. Dirt was emptied into large buckets. This process was time-intensive and exhaustive, but rewarding. A few ticks were found crawling, which caused for a minor panic, but they continued work. After buckets were filled, each bucket was brought to the sifter so that hidden artifacts could be uncovered.

As excavation was happening, Annie and Emily took turns drawing a sketch of the various artifacts and rocks as they were being uncovered on the Excavation form.

For bucket one, Sam poured the contents of the bucket onto the sifter as Hank moved the sifting device back and forth; this process surfaced items such as nails and bullet casings, letting the rest of the dirt fall to the ground. This process uncovered charcoal, nails, plastic, bone marrow, shells, and a .22 bullet casing.

- Img 7. Excavation form from trench 2, as filled out by Annie

- Img 8. Trench two post-excavation

Trench 1: Context 4

Img 9. Trench 1 being excavated

Arya, Maanya, Miyuki, Price, and Sam worked to excavate trench 1, specifically context 4. This group had a similar process to that of those working in trench 2, and followed the same excavation techniques. This group, however, was working much deeper than that of trench 2. As Maanya discusses in her fieldnotes, they conducted trail trenching–digging the site solely for its archaeological findings and potential.

Following the sifting process, this group separated findings by material, bagged findings, and labeled the bags appropriately. Some interesting finds from this group included metallic springs, a (potentially) glass coaster, some pottery pieces, and a few nails.

Interpretation:

The abundance of charcoal found could be indicative of the mill’s original time in use. In our research about mills, we have learned that they catch fire quite often because the powder released during the milling process is extremely flammable. One local mill that burned down multiple times as a result of this is the Archibald Mill – we hypothesize that the same thing could have occurred here. One further question we could pursue to seek out an answer to whether or not this is the cause of the charcoal would to be to do some sort of analysis on the walls that remain in the mill to see if they have remnants of ash on them. Another possibility is that the charcoal is not the result of a mill fire, but rather from site usage after the end of the mill’s functioning.

Additionally, we found many nails (pictured above), which were greatly rusted. Perhaps these came from the mill’s construction or mechanisms which existed within it. Furthermore, many of the nails are bent or broken, indicating that they were used for something heavy or as support. It is difficult to tell without further analysis, but given the layer at which they are buried and the damage they underwent, we are hopeful that they prove to be from the time of the mill’s use. One potential next step might be to analyze the different nails used and the construction practices of the time. We could compare this research to the nails we found to get a better idea of whether our nails come from the mill’s initial occupation or not.

As far as more contemporary occupation, we found a .22 casing, which is potentially from a more recent time than the mill’s use. With more research regarding the hunting and firearm practices throughout the last couple centuries, we may be able to figure out approximately when the bullet was fired. Depending upon the time at which the bullet was fired, it could raise a few different questions. If it is from the time of the mill’s use, then we should search the Waterford records to see if there was any news of something being fired, intentionally or unintentionally, at the mill. Alternatively, if it is more contemporary we could try to find more bullets or casings to see if we can piece together a pattern of why/when they were fired.

[wpvideo M6DTOPlg]

Vid 1. Aaron demonstrating wonderful brushing technique to excavate trench 2, while Annie ponders the realities of the earth.

Week 6 (Wednesday Lab)

Aaron, Maanya, and Apoorba

Archaeological Methods

May 10, 2019

Weekly Write-up- Week 6

Due to inclement weather, the Waterford Archaeological Team (WAT) worked on artifact cleaning inside the classroom instead of traveling to our usual fieldwork location at Waterford Mill. Our objective was to organize the artifacts into groups based on their material categories. We washed and sorted the collections that we had discovered up to this point from the fieldwalking survey, the gridded survey at the Waterford Mill site, and excavation trenches 1 and 2. Due to the variety of artifact sources, we divided ourselves into groups with each team assigned to artifacts from a particular trench context, survey unit, or gridded survey square.

Unpacking:

WAT carefully unpacked the artifacts from their bags unloaded them onto trays for thorough cleaning.

Figure 1. A cardboard box containing artifacts from the Waterford Mill Archaeological Site.

Figure 1. A cardboard box containing artifacts from the Waterford Mill Archaeological Site.

Organizing the forms:

As WAT moved on to the organizational step of the archaeological process, forms and paperwork took the central stage along with the material collections. Sam W. and Clarissa organized the forms and rechecked the data to match with the material collections. Clarissa proceeded to make an inventory for the washed and unwashed bags of materials to help accelerate the process of analysis over the coming weeks.

Figure 2. Sam W. and Clarissa maintain an organized structure for keeping track of the locations and labeling conventions for each artifact source.

Figure 2. Sam W. and Clarissa maintain an organized structure for keeping track of the locations and labeling conventions for each artifact source.

Figure 3. Sam W. and Clarissa report to Professor Knodell regarding their task. Meanwhile, Sam A. and Loren remove dirt from ceramics of Trench 2.

Figure 3. Sam W. and Clarissa report to Professor Knodell regarding their task. Meanwhile, Sam A. and Loren remove dirt from ceramics of Trench 2.

Division of labor:

Everyone divided into teams to keep track of the artifacts we were cleaning. Maanya, Arya, Lena and Miyuki undertook the cleaning process for the materials collected during the field walking surveys. Aaron, MJ, and Holland worked on material remains recovered from trenches, the primary artifacts being from trench 1, context 2. Emily, Anne, Clara, Sam A. and Loren focused on collections from the gridded surveys.

Brushing the dirt off:

This was a crucial step in the archaeological process since it enabled us to get a better understanding of what the artifacts looked like before they were buried under piles of dirt and soil. The groups used toothbrushes or a tool brush to clean excess dirt from the outside of the material. Brushing off the dirt off was essential especially for materials that could not be washed. For the metal remains, the group used subjective judgement to distinguish between diagnostic pieces and pieces that lacked diagnostic qualities. They used a toothbrush and paperclip to clean the dirt off of the surface of the diagnostic pieces, which are more valuable to archaeological interpretation than non-diagnostic pieces. We appreciated the wide range of objects that the various survey groups and excavators had collected since they each have a story to tell about the mill’s past.

Figure 4: Maanya starts off the cleaning process for her materials by brushing the dirt away using the tool brush. Taking the dirt off beforehand makes washing easier and less muddy.

Figure 4: Maanya starts off the cleaning process for her materials by brushing the dirt away using the tool brush. Taking the dirt off beforehand makes washing easier and less muddy.

Wash em clean:

Next, for all materials other than metal, we used water to finish the cleaning process. Water was avoided for metal and other biodegradable materials to prevent further erosion and degradation. We used the LDC bathroom taps to wash the artifacts clean, and wiped them off with paper towels after. This was especially difficult for hollow objects like cans, the inside of which had to be cleaned before moving on to its surface. We encountered a number of earthworms and bugs that had found a home in the unwashed artifacts. These had to be washed off before the artifact could be dealt with. Cleaning the glass and ceramic objects proved relatively easy. The objects that were collected during the rain-showers were harder to clean because the dirt was damp and stuck to the surface, whereas for the artifacts gathered on the clear days, simple dusting and brushing proved sufficient.

Figure 5: Clara and Anne team up to wash the artefacts from the gridded survey while Arya shows her solidarity by recording this wonderful moment. (You’re welcome!).

Figure 5: Clara and Anne team up to wash the artefacts from the gridded survey while Arya shows her solidarity by recording this wonderful moment. (You’re welcome!).

Drying:

Finally, the artifacts lay on clean trays to dry off. Paper towels also came in handy to speed up the process as we had limited time and a few more steps to fulfill.

Figure 6: Emily takes the assistance of paper towels to accelerate the drying process.

Figure 6: Emily takes the assistance of paper towels to accelerate the drying process.

Like with Like:

The team counted, bagged, and labeled the non-diagnostic pieces, and placed all other artifacts in a distinct bag according to material. Then, the smaller bags were placed in a larger bag labeled for the square and context from which the artifacts were recovered. We labeled the initials of the person who had undertaken the survey, the type of material placed in the bag, and the survey unit/grid that the materials prescribed to. Sam W. and Clarissa traveled to each table and documented the numbers of each material type on Clarissa’s computer, which could then be used as a data set in future analysis.

Figure 7: Good organization allows us to keep artifacts organized by their context, so that we do not lose valuable information about any of our materials by failing to record where they were originally found in site. In this image, Aaron, MJ, and Holland have created a tray of objects exclusively from Trench 1, context 2, and have also divided the objects according to their material.

Figure 7: Good organization allows us to keep artifacts organized by their context, so that we do not lose valuable information about any of our materials by failing to record where they were originally found in site. In this image, Aaron, MJ, and Holland have created a tray of objects exclusively from Trench 1, context 2, and have also divided the objects according to their material.

The future accountants:

On Thursday, Aaron, Arya, and Maanya went to Alex’s office hours where he showed us all the artifacts that had been collected by the lab groups (and gave us coffee!). Following this, we produced an inventory of which artifacts had been cleaned and which artifacts still needed to be cleaned:

Trench washed:

Trench 2, context 1- 1 bag (plastic)

Trench 1, context 1- 3 bags (glass, ceramic, metal)

Trench 1, context 2- 5 bags (metal, other, metal scrap, pottery, glass)

Trench 2, context 3- 4 bags (glass, leather, metal, ceramic)

Gridded Survey washed:

F12- 4 bags

H11- 3 bags

F-11- 1 bag of metal

F-10- 1 bag of other

H-12- 4 bags

H-13- 2 bags

H-10- 3 bags

G-11- 1 bag

G-12- 6 bags

G-13- 2 bags

Fieldwalking washed:

SU W1-01- 5 bags

SU W1-02 – 3 bags

SU W2-01- 4 bags

SU W2-02 – 7 bags

Trench unwashed:

Trench 1, context 3 – 7 bags

Trench 2, context 2- 1 bag

Gridded Survey unwashed:

G-11 (6 small bags in 2 big bags)

Fieldworking unwashed:

T2-01 – 16 bags

Blog it!

After each week of fieldwork, each member of WAT publishes a summary of his or her contribution to the project website, or blog. Finally, a designated group of team members creates a blog post each week to capture a holistic summary of all the work completed for that week, giving everyone a better sense of where we are in the process of our excavation. Additionally, this website is available to the general public for anyone interested to learn about the project.

Figure 8: Future archaeologists (from left to right: Aaron, Maanya, Arya) summarize WAT’s hard work from week 6 outside the Carleton College Classics department. WAT values civic engagement through archaeology, which is why we publish our process and research for the public to view each week on our website.

Figure 8: Future archaeologists (from left to right: Aaron, Maanya, Arya) summarize WAT’s hard work from week 6 outside the Carleton College Classics department. WAT values civic engagement through archaeology, which is why we publish our process and research for the public to view each week on our website.

Fun Fact of the week:

Alex “the Barista” Knodell makes bomb coffee. Drop by his office hours to witness the magic (Again, you’re welcome!).

Figure 9: No caption needed.

Figure 9: No caption needed.

Week 5 (Wednesday Lab)

Pre-Lab

During the Wednesday lab at the Waterford Mill site, we continued our archaeological work by continuing mapping, survey, and excavation. The class divided into three groups: a mapping group (3 people), a surveying group (2 groups of 3 people), and an excavation group (6 people).

Figure 5.1: Trekking along the railroad, mentally preparing for our surveying exploits.

Mapping

Hank, Clarissa, and Aaron were in charge of mapping for this week. The focus was first to lay out the last points for the grid. In laying out the grid, they noticed that while the points are supposed to be five meters apart, most of them were not exactly five meters apart. This discrepancy was likely caused by both human error in measuring the land and by the uneven landscape. They then took points at the corners of the excavation trenches and in the middle of the trenches to figure out the depth of the current excavation. Analyzing this depth will be useful as we later consider how artifacts and their context relate to their position or depth in the soil or ground.

Figure 5.2: Almost levitating.

Figure 5.3: A Google Earth depiction of all the points that have been mapped with the GDPS, with Tuesday lab group points in blue and the Wednesday lab points in red.

Figure 5.4: A depiction of mapping points and their correlation to their surroundings: the yellow lines represent the mill walls that were mapped, the white circles represent the excavation trenches, and the pink lines represent the survey units.

Survey

We split six people into two groups of three and each surveyed the units which were not yet surveyed. The units left were H10, H11, H12, H13, and G13. Group 1 surveyed H10, H12, and H13, while Group 2 surveyed H11 and G13. Alex advised us to survey one unit for the first ten minutes and then to start counting the artifacts we found in that survey unit. If we do not set a time limit, our surveying could last years, maybe even a lifetime. Our archeology labs only last two hours. During our survey we took pictures of each artifact and wrote down the number of artifacts we found, which we classified according to material types. We also drew a sketch of each unit to show where each artifact was found.

Survey Group 1: Loren, Miyuki, and Sam

Sam was in charge of note taking and Miyuki and Loren surveyed the unit and counted the artifacts they found. In the inner units, we more likely to find artifacts which seemed related to the site itself. In outer units, especially H13, we more likely to find artifacts thrown in the unit from the outside relatively recently. We started to think about and investigate the spatial and chronological relationship of the site and artifacts, especially in the articles of trash we found. We found different kinds of artifacts in different locations and units, and we would like to think about how the locations of these artifacts reflect on or reveal something about the different types of people who disposed of these things in these units.

Figure 5.5: The gang huddling before the big dig.

Figure 5.6: Survey Unit Form of H10

Figure 5.7: Sam and Loren eyeing the earth.

Figure 5.8: Glass lost

Figure 5.9: Glass found

Figure 5.10: Survey Unit Form of H12

Figure 5.11: Survey Unit Form of H13

Survey Group 2: Emily, Lena, and Annie

Emily was in charge of sketching, outlining product features, and Annie and Lena dug in the dirt for findings. We found a maroon palm-sized fragment of pottery, roughly 14 pieces of glass, an old bag of chips, and a tiny clamshell, among other things. Surveying G13 was particularly difficult, as prickly branches covered the ground and we had to be careful not to let the thorns seep into our clothing and prick our skin. Despite this obstacle, we did find one shell fragment, and got some good practice clearing brush. How does contemporary archaeology make it possible to reveal the relationship between the site and the people who used it chronologically and spatially?

Figure 5.12: Lena finding glass stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Figure 5.13: Dirty glass

What does the spatial distribution of the found artifacts tell us about their chronology? Can we infer anything about the people who used this site from the spatial distribution of the artifacts?

Excavation

For excavations, we again split six people into two groups of three. The first group was Price, Holland, and MJ, and the second group was Sam, Arya, and Maanya. The groups discussed with Alex about whether new 1m x 1m excavation trenches should be started, or whether they should continue working in the excavation trenches created by the Tuesday lab group. The decision they reached was to continue the excavations started on Tuesday and pick up where they left off.

Figure 5.14: Trench 1 Pre-excavation on Wed

Figure 5.15: Post-excavation at the end of the lab

The first group excavated the trench that was next to the trash pit, which was identified as trench 1. They trowelled the area and used dustpans to remove excess dirt. The trench was on a slight slope and was just above the trash dump, which made excavations a little trickier, so the dustpans were easier to use than a shovel would have been. They found a lot of rusted metal pieces, broken glass, and broken ceramics, which were all bagged, after sifting their excess dirt.

Figure 5.16a: Excavation form for trench 2

Figure 5.16b: Excavation form for trench 2

The second group excavated the trench next to the lower wall, which was identified as trench 2. They shovel shaved and trowelled the area, removing several roots and digging around embedded rocks. They found mostly metal scraps and nails and bagged them and sifting their excess dirt.

Figure 5.17a: Excavation trench 2

Figure 5:17b Excavation trench 2

This week, our finds included rusted pieces of metal, broken glass, and broken ceramics. These finds tell us that people may have gathered around this area to eat or dispose of eating or food containers. From these finds, we can learn about the material culture of the area. As the mill was an industrial site, it makes sense that we found a collection of rusted metal fragments. It also makes sense that we found so many pieces of glass as trench 1, as it is located next to a trash dump. People often dispose of glass and related materials in trash dumps. We wonder who used this site as a trash dump: men in the mills, nearby farmers, or both? Our further excavations may be able to help us answer this question. Looking into historical records to see if we can find records of this dump would also help us determine who used this dump.

Lab Highlight

About halfway through the lab, as Lena and Annie were clearing brush, Emily turned around toward the railroad track and bid an enthusiastic “Heeey!” to the void. Lena and Annie were confused. It turned out that Emily thought the goats who were bleating were people saying hello to her. As a good citizen of archeology 246, she had to return the greeting.

Week 4 (Wednesday Lab)

Pre-Lab

During class time on Tuesday, we continued our discussion of site surveying and the broader question of social organization in archaeology. Stressing the importance of documentation in the field, as well as responsible post-fieldwork information management (which would become crucial post-lab session on Wednesday) we talked through some of the ethics of the field and the irreplaceability inherent in the work. Next, we discussed the assignment “campus complexity” in small groups. Through the course of these conversations, issues of site definition variation, settlement pattern analysis, site hierarchy, tell sites, and vertical vs. horizontal approaches to archaeological analysis. We eventually moved on to consider recording methods for survey, some of which we would use in our lab section the following day. A few of the strategies we would use in lab include mapping with a tape/compass, differential GPS mapping, feature recording, site clearance, photography, transection of site into grid squares, and fieldwalking.

We were also visited by Dr. Andrew Wilson, and archaeologist and an Academic Technologist at Carleton. He gave a talk on his own experience with surface investigations in various locations, including Britain, Dhiban, and Buseirah. In the Madaba plains of Jordan, he used GIS, multi-scale historical maps, and over 50,000 digitally recorded artifact points to try and pinpoint artifact clusters. Mapping artifact clusters seems like it would be a useful exercise with our own data at Waterford. Finally, he talked in length about his use of magnetometry and DGPS, as well as ground penetrating radar. He hilariously noted how not everyone can use magnetometry equipment, because “some people just have magnetic fields about them.”

Lab Prep

On Wednesday, our lab group put all that we had learned on Tuesday to the test as we headed out to the site.

Figure 1: The Site

Expanding on the already substantial work done by the previous days lab group, we worked on clearing, laying, and documenting our site grid into 5 m² sections, marked by pink tape. We split into four main groups: site clearance, feature mapping, grid laying and documentation/differential GPS mapping.

Site Clearance Group

The site clearance group got to work immediately clearing brush and meddlesome vines from the grid area, primarily the southern and western parts of the site. The physical labor necessary for this task was considerable, but satisfying. Thorny vines, however, proved especially trying.

Figure 2: A Particularly Thorny Vine

Because of the extensive labor already completed by the Tuesday group, the site clearance group was able to start collection in the G10 grid. In just ten minutes, Clara and Loren found 25+ BB gun bullets, a metal can, a dated ceramic brick, a lump of charcoal, and a couple shards of glass in the G10 grid alone. This seems a promising omen for future finds.

Figure 3: Site Clearance in Action

Grid-Laying Group

The grid laying group added eight new grid sections to the site in total. Maanya and Owen measured distances with measuring tape, Arya was in charge of the compass and recorded bearings, and Price put down the stakes and added the flagging tape.

Figure 4: Waterford Mill Schematic Sketch

A few in this group brought up the possibility of expanding the grid for further collection in the coming weeks.

Differential GPS Mapping Group

Another mapping group used a differential GPS to plot different points around the sunken part of the site, avoiding trees. They began by labeling their points with the following notation: WM(waterford mill) and the number point (01). However, they soon realized that this would not be the most effective manner of mapping, and so revised their notation to make it more specific: for example, WMSB01, WMSB02, etc for the south building. By the end of the lab period, they had mapped out points on the south building, its adjacent west building, and the corners of some of the survey units. However, due to various constraints, they noted that their numbers did not always appear as expected, and that because they could only access some of the points, the corners could ultimately end up being numbered something like 01, 02, 03, 22. While this was not ideal, they came to the conclusion that it was a better solution than trying to guess what numbers to omit.

Figure 5: GPS Mapping in Action

Figure 6: LIDAR Waterford Mill Topography

Feature Mapping Group

The group responsible for feature mapping also split into two. Annie and Emily mapped and surveyed the larger compound on the SW side of the site, while Miyuki and Lena covered the other side of the mill wall.

Figure 7: Waterford All-Features Map

Feature Mapping/Collection Team 1: Emily and Annie

After a period of feature mapping, Emily and Annie began collecting artifacts from grids F10 and F11. Despite reporting 30% visibility they were able to find 10 metal artifacts in the F10 grid, as well as a tobacco wrapper, charcoal, and a clam shell.

Figure 8: The F10 Grid Feature Form w/Map of Feature Placement in Field

Their finds were even more numerous in the F11 grid:

Figure 9: The F11 Grid Feature Form w/Map of Feature Placement in Field

Feature Mapping Team 2: Lena and Miyuki

Lena and Miyuki were primarily concerned with features in their part of the grid, filling out eight feature forms and taking an abundance of pictures. Among some of the features they noted were:

Figures 10-13: A Road/Path (W2-02)

Figures 14-15 : An architectural fragment, or the remnants of a metal fence (W2-01)

Figures 16-17: A stone foundational wall most intact on the side parallel to the road (W2-04)

Figure 18: Concrete block with square holes where posts or “concrete toutings” may have been (W2-05)

Figure 19: A rusted pipe jutting out from the side of the mill wall likely made of iron (W2-03)

Figure 20: Concrete blocks (W2-06)

Also found were two artifact scatters, indicating high density artifact areas (W2-07, 08) (Not Pictured).

Conclusion

To conclude, we learned many new techniques during our week four lab section, putting into practice a lot of what we had read about outside of class and discussed in class. While there were plenty of challenges, the experience as a whole was rewarding and we came away with solid, useable data. With practice, we hope to improve coordination and precision in data collection. We look forward to getting back out into the field next week, this time with more suitable protection against ticks and thorns!

Week 3 (Wednesday Lab)

The class preceding our lab was primarily focused on learning about relevant archaeological survey methods. Guest speaker Neil Slifka helped the students gain a better grasp of the material as it pertained to his job as Area Resource Specialist for the Minnesota State Parks and historical sites. We talked about various highly developed technologies like Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), AIRSAR, and LiDAR, and how these can help archaeologists survey terrain beneath a forest or jungle canopy. Compared to these highly developed technologies, we also examined the role of more basic and simple survey methods like using Google Earth’s satellite images and street view functionality. We finished class by going over field walking and other methods of on the ground survey techniques, with most attention being paid to the transect method as that would be the method used during our lab.

During Third Week, the Wednesday lab section of ARCN 246 experienced our first chance at field surveying as a team. Prior to arriving at our surveying location, our class went over a few important technical aspects of survey work. We went over the use of survey unit forms for important documentation, compasses, collection bags, and pink fly tape for marking the boundaries of survey units. We also assigned tasks and roles within each of the two survey teams, including serving as team leader, serving as mapper, handing out collection bags, and marking the edges of each survey unit.

Upon getting to the survey site, a field due east of Goodhue Residence Hall and the Recreation Center (Fig. 2), and we learned how to measure ten meters by counting our steps and lined up, ten meters apart, in order to walk transects of our teams’ survey units (Fig. 3). Each field surveyor walked about fifty meters in a straight line, using an online compass as a guide to maintaining a straight line bearing 270 degrees due west across the field. The two groups continued to walk their transects as the team leaders and mappers documented the conditions, geology, and topography of the scene, noting that the site used to be used for agricultural purposes and was now a grassy field with approximately 50% visibility of the ground. Because of the rain that day, team leaders noted the overcast weather conditions and the added difficulties of the light and mud in detecting artifacts on the surface of the ground. Team leaders also handed out collection bags and collected them again at the end of each survey (Fig. 4).

During our hour in the field, each group was able to walk through two survey units. We were forced to stop early and walk through the second set of transects rather quickly because the rain became heavier over the course of the lab, and this made documentation and collection of objects more difficult as we progressed further out through the second survey unit, but this turned out alright as the general density of artifacts seemed to decrease the further the surveyors got from the path we started on. The densest region of the four survey units we worked through seemed to be the northwest corner of the field, where Team 1 began its first surveying in T1-01 (Fig. 2). Some members of the lab section discussed the possibility of an early farmhouse or other structure existing at that site at one point in time.

The units surveyed by Team 1 were 50m in length and 50m in width, with a surveyor located every 10m to maximize our chances of discovering artifacts (Fig. 1). The terrain appeared to be a cultivated field, which helped with ground visibility as there was not as much grass cover and no fallen leaves covering the ground. However, this help to visibility was counterbalanced by the rain which turned the ground into a sucking mud very quickly. Team 1 found quite a lot of tile and brick in T1-01, with a total of 66 individual bits of tile/brick and 81 individual bits of concrete, this incredibly high density of building material suggests the presence of some man-made structure in our survey unit 1. The rest of the finds appear more predictable, with only 5 bits of ceramic found (these were all piled together and found by one surveyor), 23 bits of metal (spread out more evenly between the surveyors), 32 bits of plastic, 20 bits of glass, and 9 objects that didn’t fall under any other category but were obviously manmade. Unfortunately, the survey of unit 2 was rushed by the increasing rain, and so we had to rush in order to avoid being soaked. But it appears that sector two had significantly less human artifacts, Hank found a rather large pile of bones, but we did not count them in our survey as they weren’t man-made objects and handling them was probably not sanitary. Total team 1 found one ceramic artifact, no tile/brick items, five bits of concrete, no metal artifacts, two plastic items, three bits of glass, and two items that did not fit into any other category (a baseball, and some rubber ball [possibly a stripped tennis ball]) (Fig. 8).

For Team 2’s 50x50m survey units, T2-01 and T2-02, which were located to the south of survey units T1-01 and T1-02, the most collected artifact class consisted of ceramics (Fig. 7). This team collected a total sum of 42 artifacts in the first survey unit, including 13 pieces of ceramic. One collector, Arya, found 6 pieces of ceramics within one transect. In addition to these pieces and other tiles, lithics, and plastics, our surveyors found other objects that did not fit in any category: a piece of a metal pipe and an aluminum can (Fig. 5). Like Team 1, Team 2 was rushed as we surveyed our second survey unit and collected significantly fewer artifacts. We collected 11 artifacts from this survey unit, with ceramics again being the most found class with 7 objects. This group also found 2 tiles, 1 plastic, and a baseball. It appears that this more southern part of the field was less artifact-dense, but our findings may also have been a result of the weather conditions and rushed documentation (Fig. 6, Fig. 9).

Over the course of this lab, Teams 1 and 2 learned how to measure transects, document the location and conditions of survey units, and deem which artifacts might be worthy of collection and further study. This being our first time working in the field, we learned more about both the technical work and documentation involved in field surveying as well as the difficulties that variable and uncontrollable conditions such as weather may cause for archaeologists in the field.

Fig. 1 – Team 1 survey units 1 and 2

Fig. 2 – Surveyed field

Fig. 3 – Discussing survey unit assignments and learning how to measure meters by counting steps

Fig. 4 – Artifact bags being distributed

Fig. 5 – Finding organic objects as well as man-made artifacts

Fig. 6 – Surveyors returning with bagged artifacts

Fig. 7 – Team 2 in survey unit 1

Fig. 8 – Team 1 survey unit forms

Fig. 9 – Team 2 survey unit forms