One way to conduct a non-intrusive archaeological survey is to split up the area using a grid format. A grid survey effectively allows archaeologists to divide up the site of interest among their teams and position themselves relative to the map to keep track of where they are. After our initial background and contextual work on Pine Hill Village, we used Google Earth Pro to lay a grid over the supposed area of Pine Hill Village (see map below).

The Pine Hill Village Site is located directly behind current-day Goodhue Hall in the upper Carleton Arboretum. For more historical background and maps of the area, visit this page. Although the site extends into the cleared lacrosse fields, we limited our area to the wooded section and part of the hill. Here, we assumed we would find more artifacts as these areas have not been cleared for sports fields. We spent three days in the field conducting a fieldwalking archaeological survey in groups of two across the Pine Hill Village grid. In total, we surveyed 47 units, each 10m x 10m.

To start, we used a compass and measuring tape to lay out the grid. We stretched out string to create the grid’s borders. In reference to the map below, we covered the highlighted squares. We started our grid at the bottom right corner, matching a tree in one of the previous maps of Pine Hill Village at the time of its construction.

During our archaeological survey fieldwork days, we found a variety of items that seemed to highlight both the recent recreational use and also possibly the original use of the Pine Hill Village site. We found a total of 167 items such as plastic (wrappers and bike parts), building materials (bricks and asphalt), glass (pieces of bottles), and metal. Each time we found an artifact or object, we put it in a plastic bag and labeled it with the date, survey unit, broader archaeological site information, and the names of students examining the survey square. We also recorded our findings on survey unit forms to track our progress in surveying the grid. The graph below depicts our findings:

Findings from Pine Hill Village Archaeological Survey Total: 167 items

A summary of all items found:

Asphalt: 6, Brick: 7, Glass: 29, Tile: 2, Concrete: 0, Plastic: 87, Metal: 20, Cardboard: 2, Leather Fabric: 4, Rubber: 5, Other: 5 wool, bone, foil, ball, ceramic Total: 167 Artifacts

Because the majority of what we found was trash from more modern uses of the area, we decided that the most important objects with regards to Pine Hill Village were the building materials and the glass. It seems that these are more likely to be from Pine Hill Village than much of the plastic. In case the items of this sort are from Pine Hill Village, we thought that it would be useful to look at where in the site the items were found and spatially analyze their positions in case they can reveal anything about the village. Below is a map detailing the survey units where we found building materials and glass. The blue dots depict building materials found and the red dots depict the glass.

The spatial layout of building materials and glass indicates that a housing structure could have been located around survey unit O14 as we see a higher concentration of artifacts in that location. After the grid survey, we decided to excavate (Trench 1) at survey unit S14 where a fire hydrant, possibly from Pine Hill Village, still remains. In this survey unit, we found a higher concentration of surface-level artifacts.

Blue dots indicate building materials, red dots indicate glass

Larger view of building materials/glass map

Artifacts Found: Bricks and Ceramics

One set of artifacts discovered included various building materials and other similar objects. In this section, we have included five images of items found across the survey. As we know that housing units were located on the Pine Hill Village site during its eight years of existence, we could potentially trace these objects to the village. Although we were unable to date them, we made educated guesses about their functions, such as the asphalt pieces being connected to the old road stretching through Pine Hill Village. For more information about the spatial layout of the housing units on Pine Hill Village, refer to this map.

- Large piece of reddish brick, about 12cm long, found in survey unit X16, lot 7

- Small piece of brick, 6cm long, found in survey unit X16, lot 7

The below pieces of asphalt were found in survey unit O14, lot 1. We can potentially trace their date to around 1946, when the asphalt road running through Pine Hill Village was constructed. Today, parts of the road from Pine Hill Village remain below the grassy surface. During one of our archaeological fieldwork days, we uncovered several edges determining the width of the road.

Asphalt found in O14, lot 1

Glass & Bottle Dating

A lot of the objects that we found in our grid survey of the Pine Hill Village site can be classified as modern trash. It had been thrown out or discarded by people walking on the Arb trails or others who had come to watch or play lacrosse games. However, our survey did yield a few things that were more likely to be from Pine Hill Village than the rest of the artifacts. This included building materials, like asphalt and bricks, and glass, mostly in the form of whole or broken bottles. With the limited resources at our disposal, it remains difficult to date many of the building material artifacts that we found. However, an archaeological research resource online provided information about how to date glass bottles.

While some bottles seem similar and contain little information revealing their manufacture dates, many tiny details and features associated with bottle manufacturing can help to assign a date to the bottles we found. One interesting bottle from the Pine Hill Village survey was a clear 40 oz bottle with no stickers or identifying marks beyond a cap with the label “Olde English 800” screwed to the top. Inside of the bottle was still some of the original liquid contents: a yellow liquid that appeared to be malt liquor.

Glass bottle

The first thing to look for when attempting to date a glass bottle is raised embossing on the sides or a vertical seam running down the side. This bottle had no raised embossing on the sides, but it did have a vertical side seam.

Vertical side seam

If the bottle does have this seam, the next thing to look for is whether or not the seam stretches all the way up to the rim of the bottle. This was true for our bottle, and this indicates that the bottle was machine-made rather than hand-blown. Machine-made bottles always date after 1900.

Color is the next detail to investigate. This bottle has clear, colorless glass. However, in clear bottles like this one, there is often a faint tint of color that can indicate the substances and methods used to remove the color from the glass, and it is possible to date the use of these substances and methods. The faint tint of color can be seen the best in the thickest parts of the bottle, like the base. My bottle has a slightly yellowish tint, which indicates manufacture after 1912. Since the method that leaves the yellowish tint in the glass is still used today, that puts the bottle’s manufacture date between 1912 and the present.

Yellow-tinted glass

Bubbles in the glass can also be a proxy for the bottle’s manufacture date. With regards to machine-made bottle, bubbles became more rare in the 1930s due to advances in the manufacturing process. After that, any bubbles in glass bottles became smaller and smaller as time went on. This bottle has no bubbles that I was able to find, indicating that it was made at least after the 1930s but was likely manufactured relatively recently.

After Prohibition ended in the United States, the government issued a warning to be embossed on all liquor bottles that stated Federal Law Forbids Sale or Reuse of This Bottle. Its presence on a bottle proves that it was a liquor bottle manufactured in the US during the period between 1935 and 1964. However, the bottle does not include this warning, and due to it being a liquor bottle (evidenced by the Old English 800 cap), it was not manufactured during that period. This means that the bottle was not from Pine Hill Village. Still, there is more that various features on the bottle can reveal.

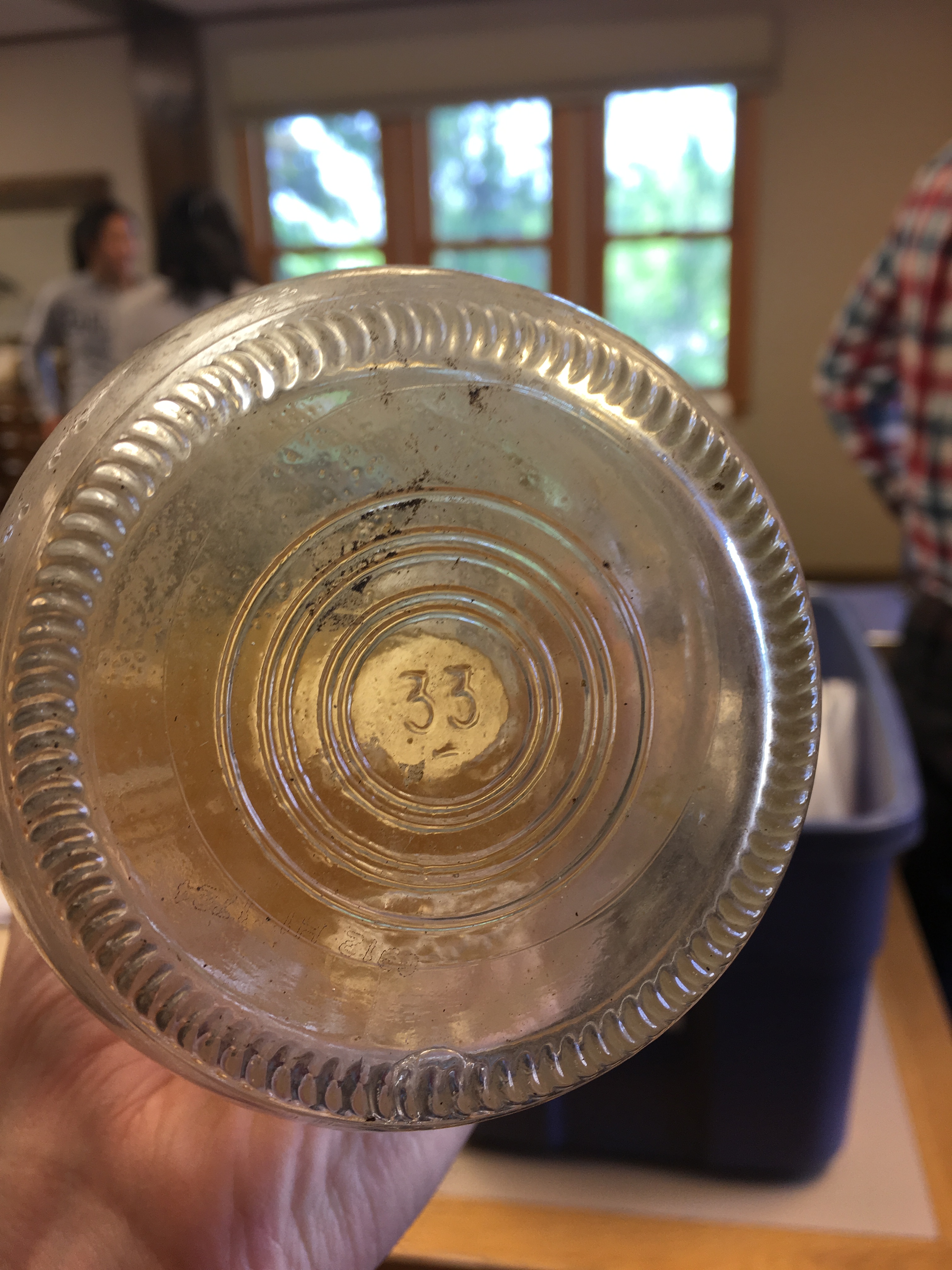

Stippling or knurling is the name given to the texturing on the base of the bottle meant to keep as little contact between the glass and the hot conveyor belt as possible. Different types of stippling can indicate different dates. The stippling on the base of this bottle resembles a series of embossed letter Cs encircling the edge. This type of stippling was first used in 1940.

Stippling on base

The most obvious identifying mark of this bottle is the cap. On the cap, the brand is labelled. A little bit of internet searching leads to the conclusion that this is a 40 oz bottle of Olde English 800 liquor, the likes of which was first introduced in 1980 and are still being made today. All of this information leads to the conclusion that this bottle was manufactured sometime between 1980 and the present, though more resources than those that we currently have available are necessary for more precise dating.

Red Wing Bottle Base

This broken-off glass base of a bottle was found in survey unit U14, lot 5. About 6 cm in diameter and labeled “Red Wing, MN” at the bottom, it appears to resemble the bottom of a Coca Cola bottle manufactured in Red Wing in the 1990s.

Red Stripe Bottle Fragments

Found in survey unit S14, lot 7, these three shards of a brown glass bottle closely resemble another full bottle found in Survey Unit V14. If we are correct in our observations, this is a Red Stripe Beer Bottle brewed and bottled by Desndes & Geddes Limited in Kingston, Jamaica. This “stubby” Red Stripe Bottle was first introduced in 1965 and was imported by Diageo and Guinness USA to Stamford, CT.

Unlabeled Bottle

This unlabeled brown glass bottle was found in survey unit U14, lot 5 and is about 24cm long. Although it appears to have had a sticker label at one point that has since fallen off, its manufacture date is difficult to determine. Its identifying features, such as its rounded shape and vertical mold seam, could prove useful to archaeologists and glass specialists. Unfortunately, we were not able to give it a definite date.

Evolution of Pine Hill Village Site

Instrumental in exposing surface artifacts for deeper exploration of an archeological site of interest, our grid survey of Pine Hill Village helped us to identify more current usages of the area located behind Goodhue Hall. Over the years, the site has changed dramatically from its original purpose. What once was a collection of houses for GIs and their families is now home to a lacrosse field and a walking trail through the woods. These new recreational uses of the site are reflected in the things that we have found there in our survey: things that have been left behind from people playing and watching games or hiking through the Arb. We found a lot of trash, including discarded wrappers and drink receptacles, as well as evidence of athletic activities, like balls and frisbees.

Crushed Mountain Dew Can

This crushed green and gray Mountain Dew can found in survey unit W15, lot 6, is evidence of the current recreational usage of the previous Pine Hill Village location. Based on its design and the archaeological research resources online, we can guess that this can is from the early 2000’s.

Golf Balls

Scattered across the grid survey, golf balls were one of the most frequently occurring artifacts found at the Pine Hill Village site. During our three survey days, we found a total of 16 golf balls. The two Spalding range, red-striped golf balls (above, top) were found in survey unit W15, lot 4. They could have been manufactured as early as 1971. Although there is no driving range close by, there appeared to be no shortage of golf balls to be found in Carleton’s Arboretum, implying that students frequently play golf in the Arb. The Pinnacle golf ball (above, bottom) was found in survey unit U14, lot 1.

Conclusion

After finding 167 total artifacts on the Pine Hill Village grid, questions arise regarding methods of storage, curation, and long-term preservation. To examine these questions, we read Morag M. Kersel’s Storage Wars: Solving the Archaeological Curation Crisis? and discussed his recommendations and critiques of modern storage solutions. The artifacts found across the Pine Hill Village archaeological grid survey will be stored temporarily within the Carleton College’s Archaeology Department before their exhibition goes on display during Fall Term 2017 on the 4th floor of Carleton’s Gould Library.

While the archaeological fieldwalking survey across the grid on Pine Hill Village’s site did not produce the same types of results as the excavation group’s findings, it remained crucial to our understanding of the Pine Hill Village site. We were able to develop a good understanding of the Pine Hill Village’s layout by using the grid on Google Earth Pro images to survey the area. After determining the types of artifacts found by surveying the grid units, we decided to excavate in three locations. We saw that the area around Pine Hill Village has shifted, now serving a more recreational purpose. During the days we conducted the survey, we encountered a diverse group of people using the area: Northfield residents taking their dogs for walks, students out for a run in the upper Arb, and frisbee players heading to practice. On its surface, the Pine Hill Village site, once housing for married veteran students after WWII, now reflects few elements of its residential past. Above all, our survey proved useful in determining where to excavate and offered insight into how the site has transformed throughout the years.

References

Kersel, M. Morage.

2015 Storage Wars: Solving the Archaeological Curation Crisis. Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies, vol. 3, No. 1, 42-54. Project Muse, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/576378/pdf.

Lindsey, Bill.

2016 SHA Bottle Dating. https://sha.org/bottle/dating.htm

Renfrew, C., and P. Bahn.

2015 Archaeology Essentials. Thames and Hudson, London.

No name.

Date N/A. Research Resources. ttps://sha.org/resources/

Created by: Elise McIlhaney and Emily Marks, Spring 2017

Archaeological Methods 246, Professor: Alex Knodell

Golf Balls found in PHV Survey

Golf Balls found in PHV Survey