Welcome to the Trench 3 page! Here you will find information about the location, stratigraphy, methods of excavation, and artefact information concerning Trench 3 of the Women’s League Cabin Site. Feel free to comment below with any questions, general musings, or your favorite Bob Dylan song!

Location:

Trench 3 is located downslope of the west side of the cabin, just past the patio area. We chose to excavate in this location because the pedestrian survey identified Survey Unit A03 as having a high density of artefacts and because we thought it was likely that a number of artefacts would have collected at the bottom of the slope. The surface of the surrounding area was littered with fence posts, wooden slabs, and even a windowpane, all of which indicated to us that the area may have also been a demolition dump site. The trench was 1m x 1m and approximately 43-45 cm deep. Throughout the excavation, we found a number of artefacts in the following categories: metal, glass, ceramic, charcoal, concrete, plastic, and other.

Stratigraphy:

What makes our trench so unique is the lack of soil change as we progressed deeper; we never actually entered a new soil type and all our decisions to switch contexts* were purely arbitrary — typically every 10 centimetres. We posit this is due to the location of the trench. Its position at the bottom of a slope makes it feel the effects of weathering and erosion. The majority of the soil in our trench is in fact likely runoff from the main pathway.

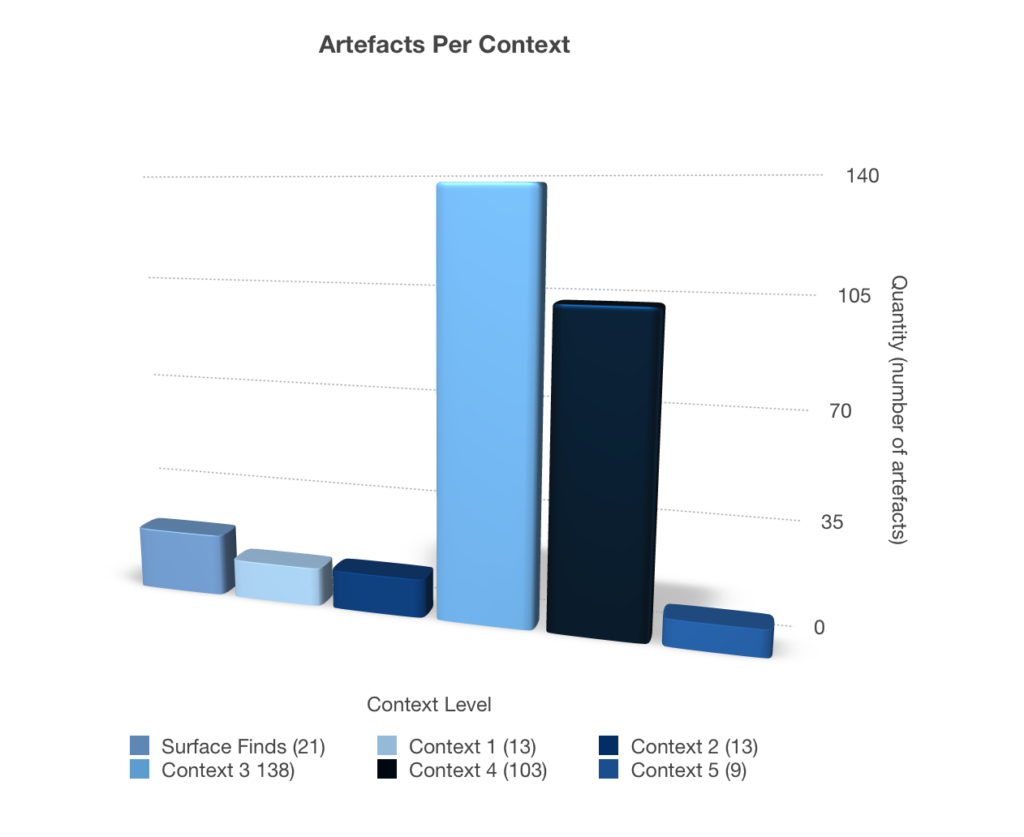

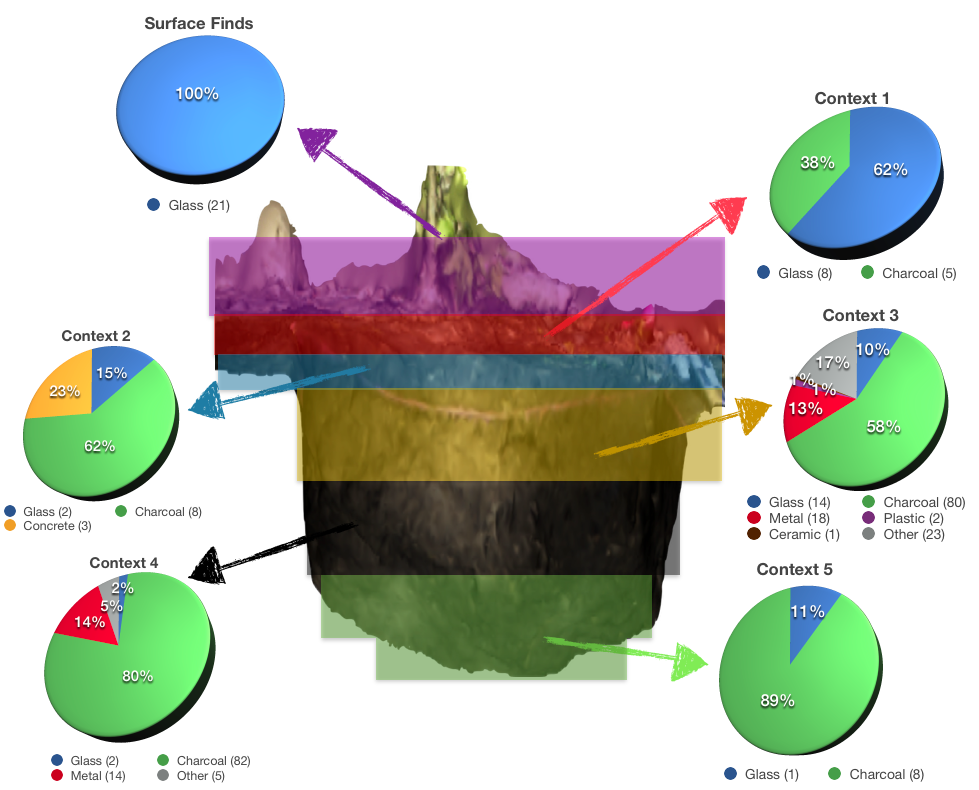

The majority of our artefacts came from Contexts 3 and 4. Most large artefacts were surface finds; several largely intact glass bottles were found on this level. Contexts 1 and 2 (approx. 10 centimetres deep) had relatively low frequencies of artefact discovery, however this is understandable given the recency of the soil present in these contexts—after all, the Women’s League Cabin has been abandoned for the past twenty years. The bulk of the artefacts were unearthed in Contexts 3 and 4 (approx. 32 centimetres deep), including all of the metal artefacts. We surmise these contexts represent the time period of the Cabin, or at the very least its final use. Accordingly, Context 5 (approx. 45 centimetres deep) had very low artefact quantities, and was likely in place before the Cabin’s existence.

*Bolded terms throughout this page are defined on the “Excavation” main page

Excavation Process:

We excavated our trench with two different methods, trowelling and shovel shaving. Before we began digging, however, we had to clear the trench area of brush, sticks, and any other impediments to digging. We then measured and marked out the area of our trench with twine and nails, and we collected any “surface finds” artefacts in the area of the trench. We used the trowel method for the first two contexts, which means we gently scraped away small layers of dirt with individual trowels. This process allowed us to thoroughly scrutinize the crucial top layers for any artefacts, large or small. As we progressed further down into context 2, we decided to begin shovel shaving. Shovel shaving is a process in which we use a flat-headed shovel to shave away slightly thicker layers of dirt. We then deposited the loose earth into buckets and proceeded to sift it with the sifter on site. Sifting (see fig. 3) requires two people to dump the dirt into the sifter, and then shake it back and forth between themselves until a large portion of the loose dirt has fallen through. At this point, the sifters then use trowels to more carefully sort through the remaining dirt for artefacts. This particular exercise was very difficult for our trench members because, due to the downslope nature of our trench, our dirt was very damp, and it often formed small clods which then had to be broken up before a team member could examine the dirt for artefacts. We continued to shovel shave and sift, with a little trowelling to even out the contexts, throughout the remainder of the excavation process.

We kept careful records of our work while in the field on excavation forms. This recording is important because it not only allows us to document exactly what we have, and thus decrease the destruction we cause, but it also gives us the opportunity to look back on our data for analysis and consideration. These forms helped us document the number and types of artefacts, the amount of soil displaced, and important data related to our trench, such as photo numbers and total station points.

Artefact Catalogue:

| Context | Metal | Glass | Ceramic | Charcoal | Concrete | Organics | Plastic | Other | Notable Finds |

| T3, Surface Finds | — | 21 | — | — | — | — | — | — | Ketchup bottle, little bottle, bottle top with cap |

| T3, C1 | — | 8 | — | 5 | — | — | — | — | Beer bottle (amber) colored glass |

| T3, C2 | — | 2 | — | 8 | 3 | — | — | — | Piece of larger bottle |

| T3, C3 | 18 | 14 | 1 | 80 | — | — | 2 | 23 | Piece(s) of larger bottle |

| T3, C4 | 14 | 2 | — | 82 | — | — | — | 5 | Piece of little bottle |

| T3, C5 | — | 1 | — | 8 | — | — | — | — | |

| Total | 32 | 48 | 1 | 183 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 28 |

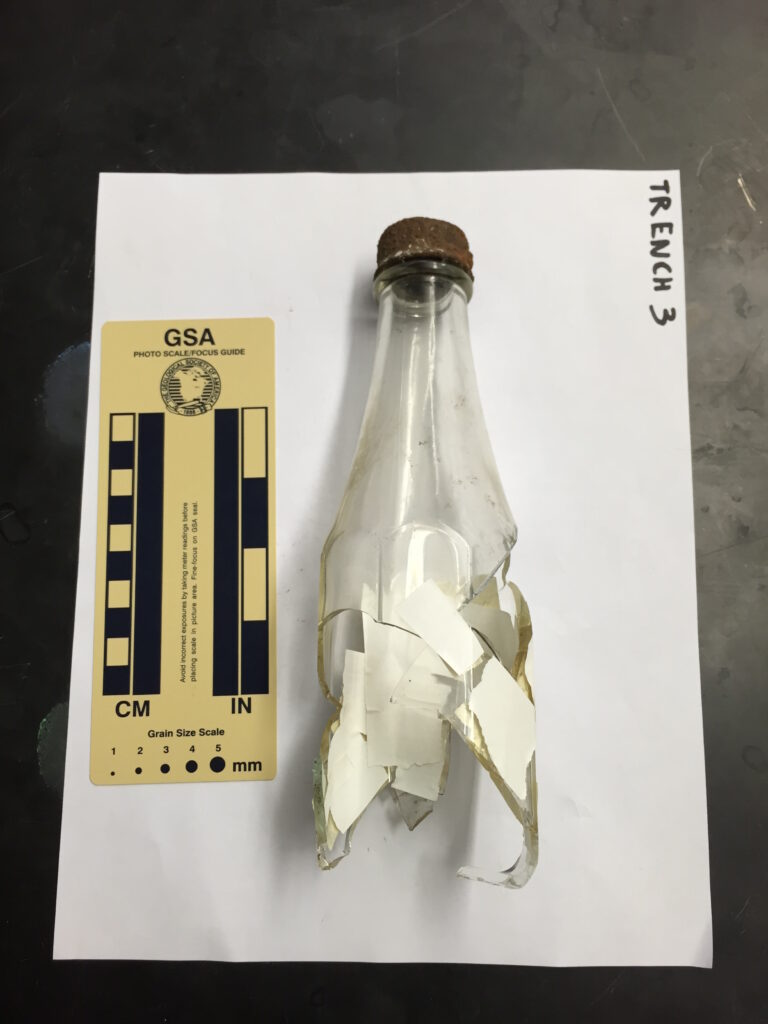

The following images are of the quantities of each material found in each context. We thought it was important to include these images in order to show the artefacts (instead of representing them with just a number) and to make the point that the process of archaeology yields very few full artefacts, most of these are fragments.

Our trench in comparison to others was graced with immense quantities of artefacts. We surmise this is once again due to the slope our trench was at the bottom of. We reason the majority of the artefacts discovered in our trench either rolled off the path over time, or were deliberately dumped there.

By far the most common material found was charcoal. The campfire area on the path explains this finding; it is common practice to throw away used charcoals and down a slope is as good a place as any. Glass shards were very common as well, they ranged in size and intactness, and many were originally from the same bottle (see Object Biographies). What appear to be remnants of beer bottles, liquor flasks and ketchup bottles were all discovered. Metal artefacts mostly consisted of rusted nails, along with a metal can and door latch (Object Biographies). The only other significant material type was ‘other’: we found a large quantity of what appears to be slate, however we cannot say for sure. Finally, trace amounts of plastic, ceramic and concrete were found in the trench, we are unable to attach any particular importance to their placement.

Object Biographies:

Bottle-

After extensive investigation, I have determined that the reconstructed trench three bottle was manufactured in the early twentieth century to hold off-brand ketchup.

SHA describes typical ketchup bottles as tall and narrow, with a narrow mouth and gently tapering shoulder. As for the body, “Most styles also had some type of molded body and/or shoulder features like vertical body ribs (common on 1890s to 1920s bottles) or vertical body side panels (typically 8 sides or more). Flat panels on the body are very typical of bottles from about 1910 to at least the mid-20th century.”

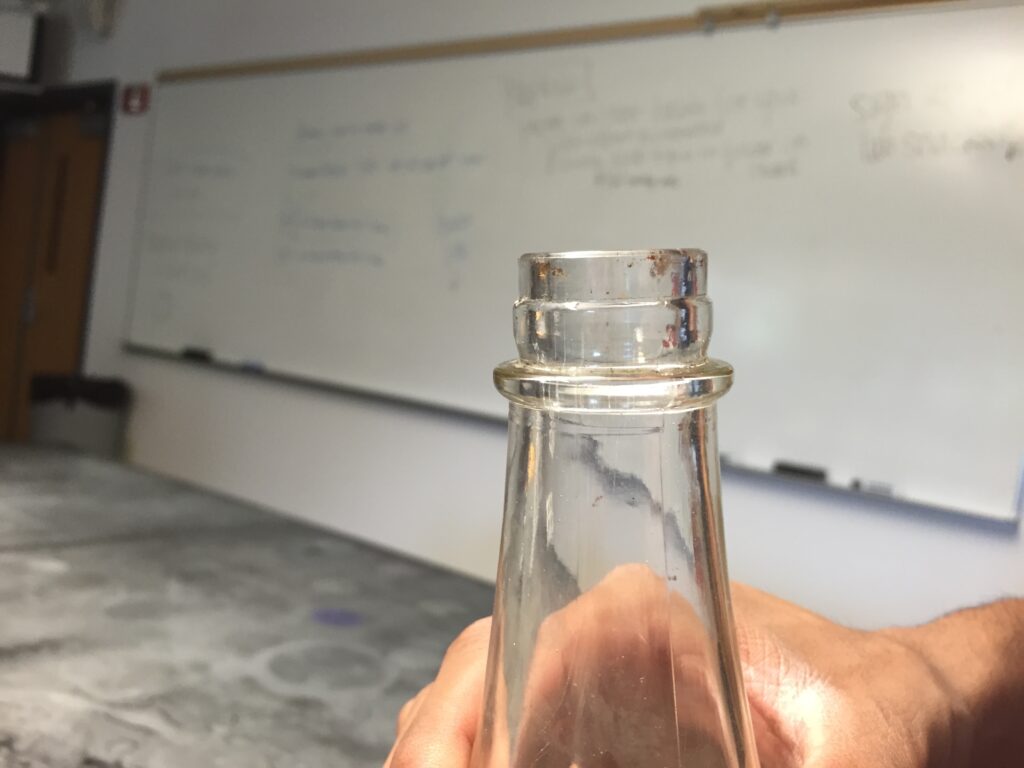

We know the bottle in question was machine-molded because it features two subtle seams running top to bottom on either side. It also features eight side panels. In fact, the bottle is nearly identical to this bottle manufactured by the Illinois-Pacific Glass Corporation in the late 1920s for Heinz. However, there are a few differences in design, most notably the lip. While the Heinz bottle features an external thread for a screw-on cap, our bottle and its cap have no thread at all. This led me to the second major finding: it was off-brand ketchup.

The Heinz bottle design was patented on March 28th, 1893. This would explain why the trench three bottle shares many elements (such as the side panels) but is not completely the same. Unthreaded caps were fairly common around the time the Women’s League Cabin was constructed, especially for condiments. However, Heinz exclusively used their patented design. This proves that one of our most sacred truths has existed for at least eighty years: college students are cheap. We might be able to assume that a visitor brought the ketchup to the cabin for a cookout – since the building had no electricity for long-term refrigeration, it is unlikely that the bottle was stored on-site. The abundance of charcoal at the site also suggests a barbecue, and raw meat definitely could not have been stored at the cabin.

Door Latch-

An artefact we found particularly interesting was a metal object found in Context 3. Initially just the main metal body was discovered, completely intact. Upon analysis in the lab, it became apparent that among the many nails unearthed in the trench, two stood out as short and flat-headed. It was soon clear that these nails perfectly fit into the object giving it the resemblance of a metal latch. More evidence of this fit, the nail’s diameter is approximately twice as thick as the latch it was placed into (Streeter 1973: 23).

While there is little literature on this type of latch available, the closest resemblance we discovered is this cast iron door bolt latch lock (left). They are both of the same material (cast iron), and while the artefact has four holes they are of an almost identical shape.

It is thus probable that the artefact we discovered was at one point connected to an iron bolt (of type similar to that in the comparison image). It was likely used in locking a door or a transom window in the cabin. While a front or back door lock would have been far too elaborate to involve the simplistic latch we discovered, our artefact could easily have locked a bathroom door or window.

While it is difficult to ascertain anything for sure, we are fairly confident that this artefact was an iron latch from the Women’s League Cabin.

Can-

In context 4, we found seven pieces of a can, one of which is a mostly intact half of the can. The large size of the can is what initially attracted us, and its mostly intact condition increased its importance. We estimate that context four was sometime around the foundation of the Women’s League Cabin (context 4 is 20-32cm deep into the soil).

Careful examination of the can seems to indicate to us that the can was most likely a soup can; it is definitely not one that would have been used for drinks, and the shape is wrong for canned meats, which usually came in oval tins (Reilly 1). A number of features of the can allow us to make this distinction. The concentric rings on the bottom of the can are typical of soup cans even today, and were not likely present on soft drink or beer cans in the past. The can has a single seam on the side that is discrete and flat, which indicates it must come from after the WWI era, when this seaming technology was invented (History of the Can).

No other identifying marks exist due to the missing top portion and rust on the base, but we can be confident in identifying this can as one most likely used for soup. Due to its placement in the soil and its seams, we can place this can chronologically in the early History of the Women’s League Cabin, most likely in the early 1940’s.

Conclusions:

Through excavating our trench, we learned about the material culture of the Women’s League Cabin. This new knowledge allows us to learn more about the Carleton and Northfield communities from the past, and informs us about our present status as students at Carleton. We also learned about the processes and methods of archaeology through survey, excavation, and recording. These results come from weeks of effort that proved well worth the time and energy in the end.

References:

“Common 20th Century Artifacts – A Guide to Dating.” Society for Historical Archaeology. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 June 2015. <http://www.sha.org/index.php/view/page/20thCent_artifacts#Cansgeneral>.

“History of the Can (timeline).” Quality By Vision: Measure Double Seams, Roll Contour Profile, Tin/chrome Coating Thickness, Bead, End Gauges. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 June 2015. <http://prev.qbyv.com/history_of_can.htm>.

PicClick.uk

Locks/Keys. Electronic document, http://uk.picclick.com/Antiques/Architectural-Antiques/Locks-Keys/, accessed June 2, 2015

Reilly, Mike. “Dating Your Tins and Cans.” Dating Your Tins and Cans. Sussex-Lisbon Area Historical Society, 14 Oct. 2012. Web. 02 June 2015. <http://www.slahs.org/antiqibles/tins/dating.htm>.

Streeter, Donald. “Early American Wrought Iron Hardware: H and HL Hinges, Together with Mention of Dovetails and Cast Iron Butt Hinges.” Bulletin of the Association for Preservation Technology. 1973: Vol. 5, No. 1, pages 22-49.